Reza Aramesh

Who is the third that walks beside you

31 May - 30 June 2007

Wednesday-Friday 12-6, Saturday 12-4

Reception for the artist: Wednesday 30 May, 6-8.30 pm

Who is the third that walks beside you? is a meditation on the nature of human identity. It questions the permanence or fixedness of identity and suggests that it is essentially ‘performative’, or, to use a phrase of Judith Butler’s in Bodies that Matter, ‘instituted through a stylized repetition of acts’.

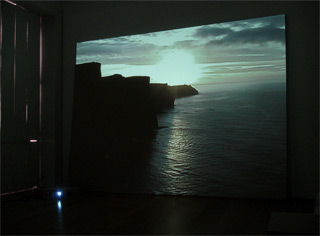

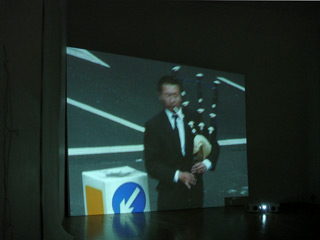

The exhibition is composed of three simultaneous video projections. Each projection is onto a screen made of boards that is propped against the gallery wall. One shows Masaki Kato, a professional bagpipe player, who plays his instrument while standing on a traffic island at the junction of Grays Inn Road and Theobalds Road, Clerkenwell. Another presents an interview with Kato in his hotel room as he prepares for the performance. The third is the static-camera image of a sunset at the Cliffs of Moher on the west coast of Ireland.

Kato is himself a person who made a radical decision about his own identity. Seven years ago, when he was a student of literature in Nagoya, Japan, he had a vivid dream of playing a musical instrument. Later he discovered that this instrument corresponded to the Scottish pipes. The dream gave rise eventually to an existential choice: Kato decided to become a bagpipe player. In 2005 he moved to Glasgow to perfect his skills.

The juxtaposing of Kato, a Japanese bagpiper playing a Scots dirge on the streets of London, with the Cliffs of Moher has an aleatoric feel which illuminates the otherwise inscrutable title of the show. It is taken from a 1964 work by William S. Burroughs, the writer, painter and spoken-word performer who championed the cut-up technique in literature, a method of achieving chance outcomes (Burroughs in his turn seems to have adapted the phrase from a passage in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land). The apparent casualness of the installation - a materialisation, as it were, of a video scrap-book - enhances the Burroughsian ambience of random possibility. Aramesh also produces the scap-book periodical Centrefold, and the show represents the extension of some of Centrefold’s principles to video mise-en-scene.

The contrast of London and Moher, two entirely dissimilar milieux, is intelligible as a statement about their difference. But it spans a narrative gap: a deliberate excision similar to those lacunae of meaning, the spaces between collaged ideas, insisted on by Burroughs. Aramesh seems to propose that it is here, in such a charged gap, in the absence as it were of an ordained life-narrative, that an individual can forge his or her own identity.

Yet the title Who is the third that walks beside you? suggests something more than a statement about individual empowerment. It embodies a disquiet which is in fact explicit in Eliot’s original lines: ‘Who is the third who walks always beside you?/When I count, there are only you and I together/But when I look ahead up the white road/There is always another one walking beside you.’ Many who have stood atop cliffs such as those at Moher (height 700 feet above sea-level) will have felt a suicidal urge; a few will have jumped: it is a suicide-spot. Kato himself is a forlorn figure amid the traffic, a still point on an ‘island’ in a city that is as profoundly indifferent to individual fortunes as it was in the time of Dickens; his tune is a lament. Identity may indeed be self-made, but at no little hazard to the individual.

Reza Aramesh’s one-person shows this year include Reza Aramesh at Watermans and a show created and curated by the artist, We’ve lost the hearts and minds, at E:vent Gallery. His work was seen recently in The Politics of Fear at Albion Gallery.